Learning to Be Wrong

by Kyndra Steinman

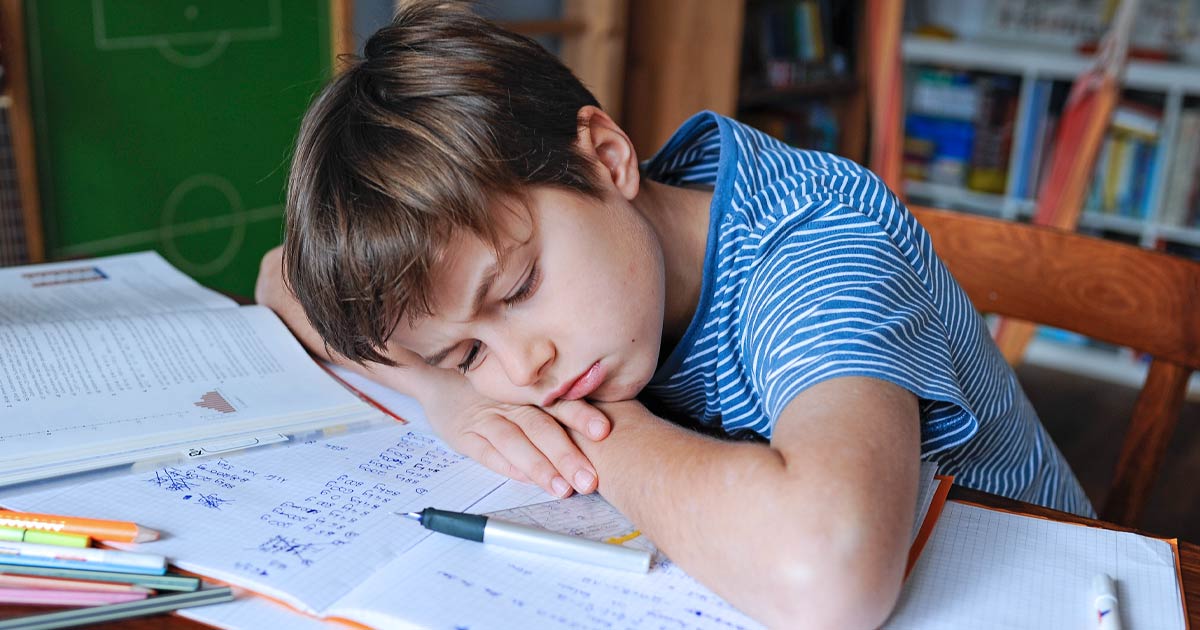

Does this type of learning ever happen at your house?

You are teaching a math lesson and ask your student, “What number, plus six, equals fourteen?”

“Seven,” he replies positively.

“No,” you say, “that’s incorrect.” And the arguing commences…

“I know that’s right; I counted!”

“You’re wrong, Mom.”

“The book is printed wrong.”

And so it goes…

Finally, you get the student to redo the problem and he finds that the answer is eight. Then the tears and frustration come out.

“I never get anything right.”

“Nothing ever goes right for me.”

And so on….

What a way to ruin a school day! And you don’t just see this response in math. Every time there is an error, the student reacts by first arguing that he must be right and the whole world wrong, and then deciding that he is incapable of getting anything right and might as well give up.

What is this? It comes across as arrogance and being easily discouraged—and certainly those heart issues are probably part of the problem—but there is another aspect that needs to be handled with careful discernment.

The Learning Challenge

Children who are highly intelligent (particularly those with Asperger’s syndrome or on the autism spectrum) struggle with being wrong about things—for two reasons—and need to learn to recognize those reasons as part of their neurological difference.

- They aren’t often wrong. These children tend to have very quick and retentive memories. If they’ve read it or heard it they will remember it and probably even remember on which page of which book they read it! My dad, husband, and seven-year-old son are all like this. I rarely win an argument based on facts with either of the adults, and the seven-year-old is fast catching up with them! Additionally, these children often are good at seeing patterns in, and imposing order on, information, so they frequently draw conclusions that are reasonable but that their parents and teachers haven’t thought of before. These conclusions vary in accuracy depending on the age and life experience of the child, but because grownups tend to not see those connections until the child points them out, the child justifiably thinks that he “knows more” than the teacher. This isn’t necessarily arrogance, but it can lead there.

- Imposing order on information is a coping mechanism. If the world is a confusing place, filled with cues that other people understand and you don’t, a natural reaction is to order what you can and derive rules based on the order. The answers that you give to math problems, or that you write down on a spelling test, must be correct since they came from the order you imposed and the rules you derived. A mistake isn’t just an error; it throws the whole structure into question, and shakes the foundations of coping with the world.

For example: My seven-year-old does his adding and subtracting not by simply combining or removing numbers, but by relating the numbers to concrete objects, picturing them in his head and asking if/then questions.

“What number plus six equals fourteen?” looks something like this: put fourteen objects in your head, color six of them,and the ones that are left are the answer but it’s too many to count in your head easily. So put ten objects in your head, color six, four are left, but I need fourteen not ten, so put twelve objects in my head, color six, six are left and fourteen is two more than twelve so the answer is seven because I need more than six.”

Of course he forgot that he needed two more than six or managed to “drop” one of his mental objects.

“Seven,” he says with absolute confidence and then reacts to my, “That’s incorrect!” by feeling his entire system of logic and order shaken.

Often, these types of reactions don’t stay in the classroom. They also carry over to sibling relationships, discussions at the dinner table, and doing chores. Eventually, as he grows, they will cause a problem in his adult life as an employer or employee, church member, and father. We have to teach him how to accept that he is wrong about something without feeling that one wrong answer destroys his understanding of how the world works.

Here are a few things that seem to help.

- Explain the importance of a teachable attitude. Keep explaining it. Every time an incident occurs, ask, “Are you willing to learn? Are you being teachable?”

- Pray with and for your child to have a teachable heart.

- Put some kind of consequence in place for continued arguing. For us, in school, work that is argued over becomes homework that I may or may not be available to help with.

- Post clear school rules somewhere where you can easily refer to them during lessons. Ours hang over the blackboard, and I just point to rules four and five as needed. This is often sufficient to stop the arguing long enough for him to think about whether he is ready to learn or not.

- Don’t be swayed by the emotions. Empathize, explain what is going on, but your responsibility is to equip the child to be an adult. You need to teach him to control those emotions, not join him in frustration and anger.

- Understand that sometimes the child may need a complete sensory break in order to get control. I have my son lie in his bed, with the lights off, curtains closed and no reading material for a specified period of time, usually 30 minutes but sometimes more, depending on the situation. The time only starts when he is quiet—the beginning step back towards self-control for him—and starts over if he calls me, starts fussing again, etc. This isn’t a “time-out” in a punitive sense, just a sensory break to help him get control. Even public schools allow for this kind of break for children who need them.

- Recognize and point out advances in control and maturity in this area. Encouragement is so very important, and even more so for children whose reaction to being wrong or getting a bad grade is to doubt their foundations. A missed word on a spelling test is still a missed word and still gets the mark it gets. But a missed word handled well should also get verbal affirmation, preferably publicly. In our house I often give a little report on our school day at the dinner table, so that my husband has a clear idea of progress and attitude and can give encouragement or instruction as needed.

- Make sure that the child understands that mistakes will not cost him his relationship with you. Shaken foundations are frightening to a child, and they need to know that their foundational relationships will not change over a bad grade or bad attitude—or over a bad interaction with you over the bad grade or attitude.

- Most of all, have patience. Many of these things change, given time and consistency, and it is up to us mothers to provide that patient, steady environment that will help our children to thrive and excel.

Kyndra Steinmann blogs at Sticks, Stones and Chicken Bones about living in a houseful of young children, special needs, discipling hearts, and abundant grace! As a homeschool graduate, she has an especial burden to encourage mothers to know and enjoy their children. Follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Pinterest.